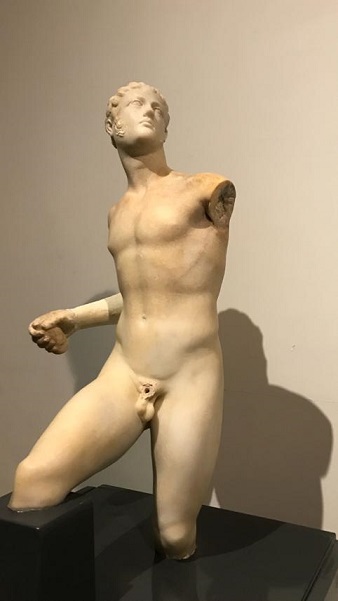

Analytically, the statue can be described as follows:

It is a standing naked figure, the most common type for royal statues (Smith, pl 3-4). A naked type showing the king with one foot, upon a support. This is the “Jason Pose” or “Sandal-loosening Hermes”, an attribution ascribed to the Lysippan school.

From literary sources, we know that this type was used for Alexander in his lifetime and it was used after him. (Plut. De Iside et Osiride 24(0.1481)). The body is slim, thus increasing the apparent height of the figure. Movement pervades the whole body. The muscles are perfect and can be clearly seen.

The back of the statue is perfectly modeled. On the figure, there is an obvious depth. The knees are projecting out of the traditional closed squared canon and are intruding on the viewer’s space.

The head has been measured 0, 13 meters and if we compare it with the total height of the statue (about 1, 10 meters), is the 1/9. This analogy is typical of the Lysiappan canon, and smaller than the previous canon of Polycleitos, which was 1/8. Pliny (Nat. hist XXXIV.65) states “Lycippos made the heads smaller than older artists had done”.

The neck is bent to the left and the eyes look upward with an aspiring glance. Plutarch (Alexander 4.1), referring to Lysippos comments: “For it was this artist who captured exactly those distinctive features, which many of Alexander’s successors and friends later tried to imitate, namely the poise of the neck turned slightly to the left and the melting glance of the eyes.” He also states that “When Lysippos first modeled a portrait of Alexander with his face turned upward towards the sky, just as Alexander himself was accustomed to gaze, turning his neck gently to one side, someone inscribed, not inappropriately the following epigram:

The bronze statue seems to proclaim looking at Zeus: I place the earth under my sway; you Oh Zeus keep Olympos”

(Ploutarch, De Alexandri Magni fortuna aut virtute 2.2.3)

These two characteristics (neck and eyes) are very intense in the statue and give the appearance of “pathos” to it.

The hair of the statue is short, but very well defined, in contrast with later portraits of Alexander with long hair, especially Roman copies; but it is more difficult to decide how closely these later works are with the Lysippan type. On the other hand, the monuments which are contemporary to Alexander, such as the Alexander Sarcophagus from Sidon (330-310 B.C) (pl. 5-6) and the Alexander Mosaic (copy of a painting of 330-300 B.C) show us that Alexander was represented with relatively short hair (pl. 7-8). The same short hair we see in Alexander of the painting frieze of the Philip’s Tomb in Vegina (pl. 9). These representations which refer to Alexander’s lifetime, give him shorter hair styles, while many posthumous portraits have longer hair, that may have divinizing connotations.

Moreover, some of Alexander’s contemporary portraits like Azara and Erbach herms (pl.10-11) have hairstyles, which in life he may didn’t have. That means that his real hairstyles could have varied widely.

But the most important feature in the hairstyle of the statue is the Anastole. This is a distinctive arrangement of the hair, over the forehead, a quiff of hair standing up with a slightly off-centre parting. This Anastole of the hair, Plutarch records, was the distinctive feature of Alexander’s physiognomy (Pomp 2.1). It seems to be considered as Alexander’s personal attribute and it is generally not used by later kings.

The sideburns on the face of the statue were a feature not very common in the portraiture of Alexander. The most important monument as the original of which was contemporary of Alexander, was, as mentioned before, the Alexander Mosaic (pl. 8). Alexander is shown bareheaded and armored, fighting on horseback. This picture, whether made in Alexander’s lifetime or not, at least, pretends to be a circumstantial representation of him in his lifetime. He is shown with long sideburns. Besides, a lot of portraits of Alexander like Azara herm, Erbach and Dresden Alexander (pl.10-11-12), or Capitoline head (pl. 13) have either sideburns or long hair in front of the ears.

The most important attribute of the statue is the two – not one – diadems (headbands), one narrow band in the hair and another one in the forehead.

A lot of literary sources (Smith, 1988 and others) attests that the diadem (diadema) is the main royal symbol of Hellenistic kings and that it was a band of white cloth worn about the head. Alexander was the first Macedonian king to wear it as an exclusive emblem of kingship. It became the symbol of his new status as “King of Asia”.

Two sources, Diodorus Siculus (4.4.4) and Pliny the Elder (NH7.191), say that the god Dionysos “discovered the diadem that he wore it to symbolize his conquests in the East and that Kings took it over from him”.

However, the form of the royal diadem is not directly copied from that of Dionysos. The god wears his headband lowdown on his forehead, while the Kings wear it further back in the hair. For this association of the diadem, there is archaeological evidence. On Ptolemy’s posthumous Alexander coin portraits the king wears an elephant head dress and a flat diadem precisely as worn by Dionysos. Alexander’s and Dionysos’ headbands are here clearly equivocated. (pl. 14-15-16)

Smith (1988) states that Dionysos was important to Alexander and remained so for the later kings. He was a conquering god and gave the divine model for the conquest of India and Asia. The similarity of the eastern conquest and of the headband’s form to those of Dionysos promoted the additional meaning of association with that god. Dionysos’ campaigns became a divine precedent and comparison for Alexander and this is the reason that he adopted the diadem as a royal symbol.

Last we have to point out that the ears of the statue are remarkably well formed and the mouth is finely shaped.

The execution of the sculpture is of fine quality and the study and comparison of the stylistic features of the statue give us the possibility to date it in the Early Hellenistic Period (end of 4th century B.C) and we consider that it was possibly made by the school ofLysippos in Alexandria.